By Joseph Trevithick | The War Zone

A new counter-drone focused variant of the 8×8 Stryker light armored vehicle armed with a laser directed energy weapon, laser-guided 70mm rockets, a 30mm automatic cannon, radars and other sensors has broken cover. Defense contractor Leonardo DRS and its industry partners are actively pitching the vehicle to the U.S. Army, which is looking to significantly grow its short-range air defense capabilities in the coming years. That service is also very interested in new laser-armed options, specifically, after lackluster field tests of a different Stryker-based system earlier this year.

Leonardo DRS, the U.S.-based subsidiary of Italy’s Leonardo, released a video, seen below, detailing what it is currently calling the Counter-Uncrewed Aerial Systems Directed Energy (C-UAS DE) Stryker earlier today. The company says seven other partners – BlueHalo, EOS Defense Systems USA, Northrop Grumman, BAE Systems, Arnold Defense, AMPEX, and Digital Systems Engineering – contributed to the development of the prototype in around eight months.

The laser directed energy weapon, a 26-kilowatt version of the LOCUST from BlueHalo installed on a retractable mount on top of the rear of the hull, is clearly the centerpiece of the new counter-drone Stryker prototype.

“It’s going to provide a directed energy capability that can kill group ones, twos, three UASs at very long range,” Ed House Senior Director of Business Development at Leonardo DRS says in the video.

Per the U.S. military’s definitions, drones in these three categories, collectively, can weigh up to 1,320 pounds, fly at altitudes up to 18,000 feet, and get up to top speeds of 250 knots. BlueHalo does not appear to have disclosed a maximum engagement range for the LOCUST.

The C-UAS DE Stryker also has a four-round launcher from Arnold Defense for 70mm laser-guided Advanced Precision Kill Weapon System II (APKWS II) rockets on a semi-retractable mount on top of the left side of the rear of the hull. This is a combination that is found on other counter-drone systems, including L3Harris VAMPIREs now being actively employed in Ukraine. APWKS II rockets with new proximity-fuzed warheads optimized for knocking down uncrewed aircraft are in the works.

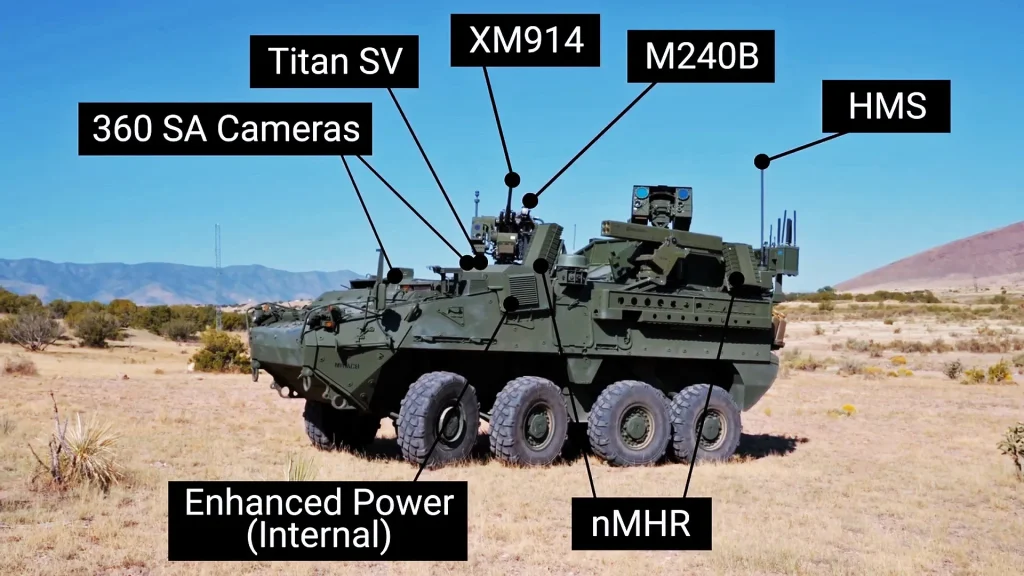

The Stryker prototype from Leonardo DRS and its partners also has an EOS R400-series remote weapon station armed with a 30mm XM914 automatic cannon and 7.62x51mm M240B machine gun on top of the front end of the hull. The XM914 is another increasingly common feature in counter-drone systems and can now fire proximity-fuzed shells, further increasing its effectiveness in this role.

The cannon’s manufacturer Northrop Grumman just recently rolled out a new dual-feed system that allows operators to remotely switch between two ammunition types, such as the proximity rounds and ones better suited for use against targets on the ground.

BlueHalo has also supplied a Titan SV system for the new Stryker prototype, which is a radiofrequency sensor to help detect and track hostile drones. In addition, the vehicle also has Next-Gen Multi-Mission Hemispheric Radars (nMHR), which are small form factor active electronically scanned array (AESA) types, as well as a 360-degree array of cameras, to help spot, classify and track targets. The promotional video labels another antenna at the rear as an “HMS,” but it is not immediately clear what that system is.

No explicit mention is made in the video about networking capabilities, but being able to feed in targeting data from off-board sources, including other C-UAS DE Strykers, and/or share the information that its sensor suite is collecting with other assets would make good sense.

Still, it is “this directed energy [that] gives commanders options. It increases the stowed kills [magazine depth] available to a unit commander, and this is technology that’s available to the warfighter today,” House stresses in the video. “You can see we’re out in the desert in New Mexico now. We’ve shot several drones down with the laser weapon system.”

Functionally unlimited magazine depth, which Leonardo DRS’ House refers to in the video, is regularly cited as a key benefit of laser directed energy weapons, as well as high-power microwave types, when compared to traditional guns or surface-to-air missiles. There is also some amount of cool down/recharge time between ‘shots,’ but each engagement costs dollars rather than the tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of dollars compared to more traditional surface-to-air interceptors. Firing traditional guns can be costly, as well.

Lasers are not without pitfalls, however. In general, they are sensitive to smoke, clouds, rain, and other environmental factors that can disrupt the beam and reduce its effectiveness. The beam’s power also drops the further away it gets from the source. Directed energy weapons often come along with substantial power generation and cooling requirements, as well.

Though the technology has advanced by leaps and bounds in the last decade, U.S. military laser directed energy weapon programs, in particular, have been experiencing new and significant reality checks in the past year or so. This includes issues uncovered with another Stryker variant the Army has been acquiring already, called the Directed Energy Maneuver-Short Range Air Defense (DE M-SHORAD), which is armed with a 50-kilowatt laser weapon from Raytheon. Four of those vehicles were deployed to the Middle East for a field test in March, according to Breaking Defense.

“What we’re finding is where the challenges are with directed energy at different power levels,” Dough Bush, Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisition, Logistics, and Technology, told members of Congress in May, per Breaking Defense. “That [50-kilowatt] power level is proving challenging to incorporate into a vehicle that has to move around constantly – the heat dissipation, the amount of electronics, kind of the wear and tear of a vehicle in a tactical environment versus a fixed site.”

At that time, Bush that “some” unspecified users were seeing other laser weapons emplaced at fixed sites “proving successful.” The Army Assistant Secretary did not name those systems. It is worth noting here that the service has already procured at least two 20-kilowatt LOCUST variants, called Palletized High Energy Lasers (P-HEL), and sent them overseas for limited field testing.

“We’ve worked with industry to increase reliability across a number of those systems,” Army Lt. Gen. Robert Rasch, head of the service’s Rapid Capabilities and Critical Technologies Office (RCCTO), said in a more recent interview with Breaking Defense in August. “For the enduring high-energy laser, we believe — based on what we’ve seen and collected data – that industry is ready to produce systems that can reach the reliability levels and the affordability levels, to get in that group one through three UAS range.”

This certainly seems to be what Leonardo DRS and its partners are aiming for now with the new C-UAS DE Stryker.

“What this shows is when industry works together we can help the army solve problems, and, in this case, we’re moving directed energy forward for the Army,” Leonardo DRS’ House says in the video released today.

The Army is in the midst of a larger push to expand and modernize its air defense capabilities, especially shorter-range systems, and with a heavy focus on defeating drones.

In addition to the DE M-SHORAD Stryker, the Army has also been fielding a baseline M-SHORAD Stryker variant, now named the Sgt. Stout, which is armed with a combination of Stinger heat-seeking short-range surface-to-air missiles, radar-guided AGM-114L Hellfire missiles, and an XM914 cannon, as well as an array of small AESA radars. Sgt. Mitchell William Stout gave his life during the Vietnam War protecting his fellow soldiers from a grenade and was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

The original M-SHORAD vehicle and the DE M-SHORAD are also known as Increments 1 and 2 of the overall M-SHORAD program. Increment 3 is focused on integrating a replacement for the venerable Stinger, which you can read more about here, into the family of the systems.

Increment 4, the requirements for which the Army publicly laid out in May, calls for a new, lighter system that can be air-dropped or lifted by helicopters to better support airborne and airmobile operations. The Army has said that the Increment 4 system could be fitted to a 4×4 Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV), an uncrewed ground vehicle, or a combination of both depending on the exact configuration of the components. The future Stinger replacement, Raytheon’s Coyote counter-drone interceptor, APKWS II, and the XM914 have all been presented as possible armament options.

The idea of porting over the Incerment 1 M-SHORAD system onto a variant of the tracked Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV) has also been discussed. The Army has also been eying a Sytryker equipped with a high-power microwave directed energy weapon for use against drones.

Beyond M-SHORAD, the Army also has a growing force of Mobile, Low, Slow, Unmanned Aircraft Integrated Defeat System (M-LIDS). M-LIDS currently consists of various components, including Coyote interceptors and XM914 cannons, as well as electronic warfare systems and sensors, split between a pair of 4×4 M-ATV mine-resistant light tactical vehicles. The service is now moving to consolidate M-LIDS onto a single Stryker. This, in turn, is causing the line between the dedicated counter-drone M-LIDS and the broader short-range air-defense-focused M-SHORAD efforts to become increasingly blurred.

Threats posed by drones, including weaponized commercial types, are not new, as The War Zone regularly highlights. However, the ongoing war in Ukraine has been central to a clearer understanding of these issues finally entering the mainstream discourse. The regular use of various tiers of drones by both sides of that conflict has caused an explosion in demand for new and improved capabilities to destroy or at least disrupt uncrewed aerial threats. The need now to defend tanks and other armored vehicles against drones, especially highly maneuverable first-person view (FPV) kamikaze types, has become particularly visible. On-vehicle capabilities and ones that can be used on the move are increasingly critical, as you can read more about in these past features.

The fighting in Ukraine has also underscored the need for layered defenses to help tackle different kinds of drones and large volume attacks. Its worth pointing out here that high-power microwaves offer advantages over lasers when it comes to engaging swarms. Swarming and other capabilities, further enabled by advances in artificial intelligence, are pushing drones, in general, toward a major new evolutionary, if not revolutionary moment. Increasingly more capable uncrewed aerial systems are set to continue proliferating globally, too. At the same time, the barrier to entry when it comes to acquiring and employing weaponized commercial drones, which can still be very threatening, remains extremely low.

This is a reality that is not lost on other branches of the U.S. military beyond the Army. In terms of ground-based systems, the U.S. Marine Corps is also particularly active on this front. That service has plans now to at least test a LOCUST-equipped JLTV of its own, as well as a high power microwave system one of those 4×4 vehicles can tow in a trailer.

Still, despite the obvious flurry of activity, the Army, as well as the rest of the U.S. military, continue to very much lag behind in their efforts to actually field various tiers of anti-drone defenses. This was underscored just recently by the appearance of an apparent Chinese-made laser directed energy weapon that is similar in some respects to the LOCUST, at least on paper, in actual use in the Iranian capital Tehran along with other new counter-drone capabilities. The actual capabilities that system offers are unclear, but it does highlight the active work that is going on in this arena now outside of the United States, especially in China.

As already noted, the Army, especially, is trying now to really push forward with dramatic expansion of its air defense and counter-drone capabilities and capacity. Time will tell, but C-UAS DE Stryker, or a similar configuration, could well be part of that future ecosystem.